Just to be clear: I have nothing personally against David Einhorn. I am just wondering how he comes up with his underlying valuation assumptions these days.

I already had issues with funding cost assumptions at AerCap as well as his return assumptions for SunEdison.

Now I came across his latest pitch for Consol Energy this week. This is the slide which explains the value of the coal business:

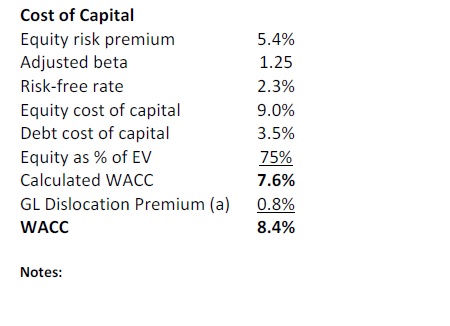

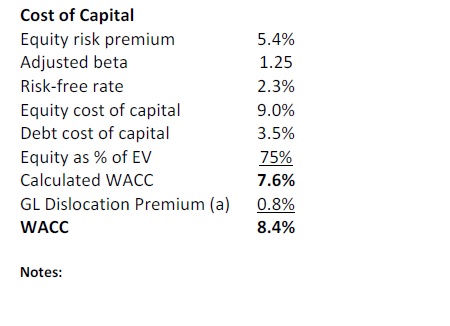

Without going into the other details, the question here is of course: How the hell did he come up with a WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital) of 8,4% ?

The WACC is supposed to be the blended total cost of capital of a company, including both, debt and equity. For Consol Energy however the obvious problem is the following: Their bonds are trading at a level of 12-15% p.a. Even if we us an after-tax figure of maybe 8-10%, even the after-tax cost of debt is higher than the assumed WACC.

As the cost of equity has to be higher than senior debt (it is more risky), there is no way in ending up with a WACC of 8,4%. Maybe some of my readers can help me out if I am missing here something, but I am pretty sure that 8,4% is not the right number for Consol’s cost of capital. He uses the same WACC later for the shale gas part of the company, so it is certainly not a typo:

On his website he then explains how they (or his intern) came up with the WACC (slide “A-1”):

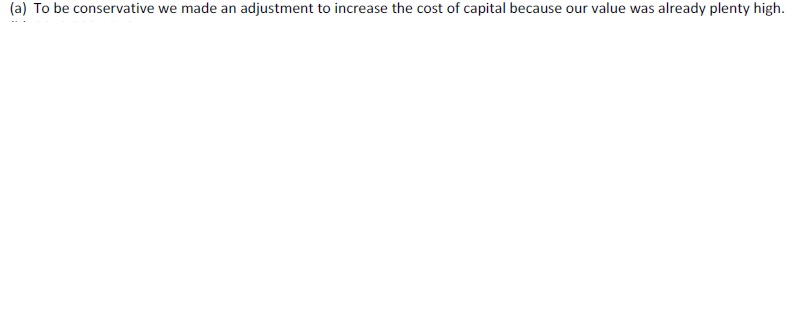

The real joke however is to be found a little bit below:

Edit: Now that I know that it was meant as a joke it reads somehow different 😉

So he somehow believes that his WACC is actually conservative.

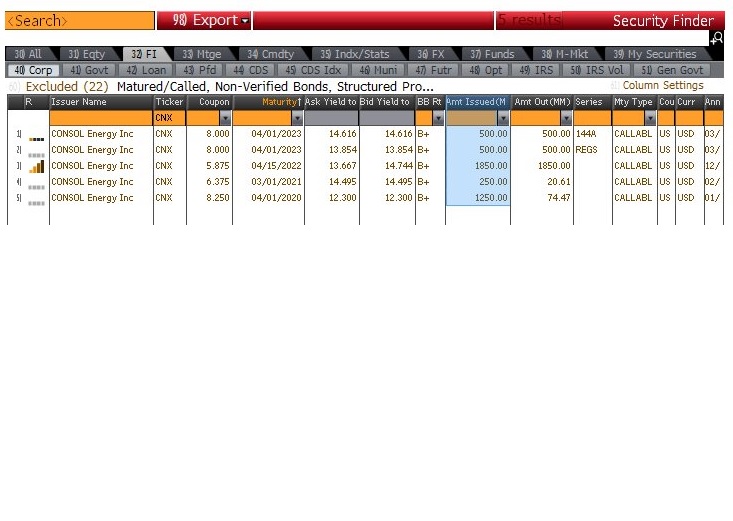

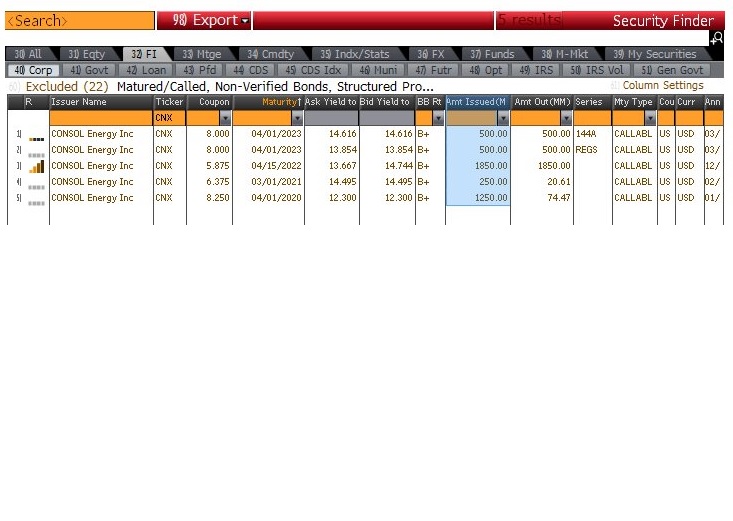

Let’s look at some “real world” data. This is the overview of Consol’s currently outstanding bonds:

The average yield based on outstanding amount of Consol’s bonds is 14,5%, a full 11% (or 1.100 basis points) higher than in Einhorn’s calculation. As I have said above, the cost of equity has to be higher than the cost of debt as thee is no protection to the downside. So if we use Einhorn’s quity risk premium of around 6%, we would get cost of equity of around 20,5%.

Based on Einhorn’s weighting, we would get a WACC of (20,5%*0,75) + (15,5%*0,65*0,25)= 17,73%, roughly speaking double the charge that Einhorn uses. You might say this is conservative but in effect it is just realistic and based on current market prices.

Even at issuance, Consol’s cheapest bond had a 5,875% coupon, far above the assumed 3,5%, so it is not even a question of current market dislocation.

Either Einhorn assumes implicitly that cost of capital goes down dramatically or he has some “secret” that I don’t know. If I look at Einhorn’s last pitches, especially AerCap, SunEdison and Consol, there seems to be a common theme: He is always pitching capital-intensive companies with significant debt where he assumes pretty low cost of capital in order to show upside.

So what he seems to do these days is effectively betting on low funding costs which, at least for SunEdison and Consol didn’t work out at all.

In my opinion, this has nothing to do with value investing. Value investing requires to make really conservative assumptions to make sure that the downside is well protected as first priority. For those leveraged, capital-intensive businesses however, the risk that you will get seriously diluted as shareholder in those cases is significant, there is no margin of safety. On the other hand I somehow admire his Chupza. Standing in front of a lot of people who paid significant fees to hear the “Hedge Fund honchos” speak and pitching such a weak case with unrealistic assumptions is brave.

Of course a stock like Consol can always go up significantly after dropping -75% year to date, but the underlying analysis is really flawed. I would actually like to ask him if he really believes in those assumptions or if he just didn’t pay any attention to the details. This would be really interesting.

Maybe a final word on this: I am always criticising David Einhorn on his assumptions. Which is easy because he actually is very transparent about them. Many other Hedge Fund managers just tell nice stories. I am pretty sure that in many cases the assumptions behind those cases are not much better.